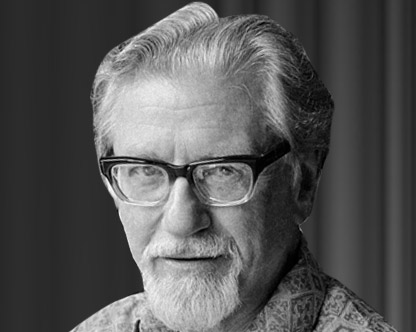

John Hewitt

John Hewitt was born in Belfast in 1907 into a Methodist family. He was educated at Agnes Street National School (1912–19) where his father was principal and then briefly at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution before moving to Methodist College (1920–24). In 1924 he undertook a degree in English at Queen’s University, Belfast, which he interrupted by taking a teacher training course at Stranmillis College (1927-29) before graduating from Queen’s in 1930.

Hewitt started to write while still at school and many of these early poems show the influence of his father’s radical socialist beliefs, which Hewitt himself would adhere to. His earliest publications were in the Irish Labour Party journal ‘The Irishman’ and the Communist Party's ‘Workers’ Voice’ as well as, more conventionally, in the Queen's newspaper ‘Northman’. His first fully literary publication was in George Russell’s ‘Irish Statesman’ in 1929.

In 1930 he took up the post of Art Assistant at the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery where he stayed until 1957, when he was appointed Art Director of the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry. One consequence of Hewitt’s combined interests in socialism and art was that he travelled widely both to attend socialist gatherings and to visit art galleries. It was during an exhibition at the Belfast Museum that he met Roberta Black and they married in 1934. Together they engaged in a wide range of cultural and political activities. They were founder members of the Belfast Peace League and members of the British Civil Liberties Union and the Left Book Club. Cultural activity usually centred on Hewitt’s concern about the inward-looking philistinism of the North and the ways in which this underpinned the troubled relationships between what Hewitt would call those of Planter stock and the native Irish in the North.

In 1934 he helped to form the Ulster Unit with artists such as Colin Middleton, John Luke, (about whom he would later publish monographs in 1976 and 1978) and George McCann. This looked out to the London-based Unit One (the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery staged a Unit One exhibition in 1935) and to movements such as the Bauhaus. While the outbreak of the Second World War meant that Hewitt was largely confined to Northern Ireland, it also enabled him to discover aspects of the North and led to the development of regionalist ideas influenced by Patrick Geddes and Lewis Mumford.

In 1943 he was a founder member of the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts for which he would continue to work until 1957. Throughout this time Hewitt was consistently writing poetry though most of his publication were in journals, most notably the autobiographical poem ‘Freehold’ in the literary magazine ‘Lagan’ in 1946. Here, and in essays such as ‘Painting in Ulster’ (in Robert Greacen’s ‘Northern Harvest’, 1944), ‘The Bitter Gourd’ (‘Lagan’, 1945) and ‘Regionalism: The Last Chance’ (‘Northman’, 1947), Hewitt develops the idea of the region as a livable locale to which all its inhabitants can give allegiance.

His first full collection of poetry, ‘No Rebel Word’, was published in London in 1948. In 1951 he presented a thesis to Queen’s on ‘Ulster Poets, 1800–1870’ and was awarded an MA. A revised version of this would eventually appear as ‘Rhyming Weavers and Other Country Poets of Antrim and Down’ in 1974. Professionally his life appeared to be on an upward trajectory when he was promoted in 1950 to Deputy Director and Keeper of Art at the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery. This would be followed, however, in 1953 by the disappointment of being passed over for the role of Director - the story behind this is told in ‘A North Light’, Hewitt’s autobiography. This book was not published until 2013, though the relevant chapter appeared in the ‘Honest Ulsterman’ in 1968, in which Hewitt draws a comparison between the Belfast Unionist establishment and McCarthyism. He remained as Deputy Director until he was appointed to the Directorship of the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry, where he stayed from 1957 to his retirement in 1972. Coventry, with its Labour-controlled council and socially progressive post-war rebuilding, was a congenial place for Hewitt but he retained close links with the North. He acted as poetry editor for ‘Threshold’ (1957-1962) and was elected to the Irish Academy of Letters in 1960. He also continued to publish poetry including ‘The Day of the Corncrake’ in 1969 which was inspired by the Glens of Antrim, where he and Roberta spent many of their summer holidays.

On his retirement in 1972, he and Roberta returned to Belfast, despite its increasing political violence, where he found himself regarded as an elder statesman by the new generation of writers who had emerged in his absence. He also found that, in the Arts Council-supported Blackstaff Press, there was finally an outlet for local writers. Hewitt, along with John Boyd and Sam Hanna Bell, benefited from this by the publication of collections of old and new poems as well as a volume of prose writings, ‘A History of Art in Ulster’. The death of Roberta in 1975 was a major blow, but his reputation was being cemented by the spate of publishing and overdue awards and prizes. These included honorary degrees from both the new University of Ulster (1974) and Queen's University (1983), where has had served as the first writer-in-residence (1976-79), along with his election as Vice-President of the Irish Academy of Letters (1975) and the award of its Gregory medal (1984).

Perhaps most fittingly, he was made a freeman of the city of Belfast in 1983. Shortly after his death in 1987, the John Hewitt Summer School was established in the Glens of Antrim, which continues, after a move to the city of Armagh, to this day.

‘A Little People’ and ‘The Mortal Place’

Dated by Frank Ormsby in the ‘Collected Poems’ (1991) as being written in June and August of 1986, these are the last poems Hewitt wrote. They were uncollected until the appearance of Ormsby’s volume. Each returns to frequently-voiced themes in Hewitt’s writing: the situation of those of Planter stock in Ireland, and the ways in which boyhood landscape have been re-written by later violence.

EH